Dog sled arriving in Knik carrying gold from Iditarod, January 12, 1912. Library of Congress

Parts of the historic Iditarod Trail had been used by Native Alaskan dog drivers for centuries, but the 1000-plus mile route associated with today’s race came about largely as a result of Alaska’s gold rush in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Originally called the Seward-to-Nome Mail Trail, it ran from the southern shipping port of Seward north through the Alaskan interior and on up to Nome on the Bering Sea Coast. The trail connected the various settlements, trading posts, and mining camps that popped up as prospectors from around the world descended on Alaska, making it possible to move people and freight and deliver mail. Explorers, surveyors, and prospectors had learned from the region’s indigenous groups that sled dogs were the most reliable means of transport during winter months. The trail became associated with the town of Iditarod after a gold strike there on Christmas Day, 1908. (The word ‘iditarod’ is an Anglicized version of the Ingalik word ‘haiditarod,’ meaning ‘distant place.’)

That same year, the first official sled-dog race in Alaska, the All-Alaska Sweepstakes, was held in Nome. The race ran from Nome to Candle and back, a distance of over 400 miles. One of its winningest mushers was Norwegian-born Leonhard Seppala. Seppala came to Nome during the gold rush there in 1900 and worked for a company sledding freight and supplies. He won the race three times, in 1915, 1916, and 1917.

Leonhard Seppala with his lead dog Togo

However, Seppala is more famously remembered for participating in what came to be known as the Great Serum Run of 1925. The winter of that year, a diphtheria outbreak in Nome threatened the city’s population, especially its indigenous inhabitants who had never been exposed to the disease. The last ship into the port before it froze over did not include a critical supply of antitoxin that had been ordered. With the only two airplane pilots capable of navigating the dangerous Alaskan winter weather traveling out-of-state, the Iditarod Trail became the only means of access to Nome. Relay teams of mushers and sled dogs were set up to transport serum from Nulato, in the east, to Nome. Seppala mushed the longest stretch of this run and subsequently became something of a legend in Alaska.

Dorothy Page, the “Mother of the Iditarod”

During World War II, the U.S. Army used sled dogs for transport and search-and-rescue missions. But after the introduction of the snowmobile in the 1960s, dog sledding was on the wane, even in the native villages. The Iditarod Trail had fallen into disuse. Then a New Mexico transplant named Dorothy Page, an avid fan of sled-dog racing, came up with the idea of putting together a race to commemorate the centennial of the United States’ purchase of Alaska from Russia. Initially, Page had little luck getting dog mushers interested. She then approached Joe Redington Sr. Redington was one of the last dog sled freighters. He had worked for the U.S. Army doing search-and-rescue missions and salvaging airplanes that had gone down in the Alaskan interior. Like Page, Redington wanted to preserve sled-dog culture. Since the 1950s, he had been lobbying to make the Iditarod Trail a national historic trail, and he felt a commemorative race would help bring attention to his efforts.

The first race was held in February of 1967 and ran 25 miles across a stretch of the old Iditarod Trail between Wasilla and Redington’s hometown of Knik. Leonhard Seppala was invited to be the race’s honorary marshal. Tragically, Seppala died shortly before the race took place. The race was named in his honor, the Iditarod Trail Seppala Memorial Race.

Joe Redington Sr., the “Father of the Iditarod”

By 1969, interest in this short precursor to the Iditarod had diminished. But Redington was determined to keep both dog mushing culture and the Iditarod Trail alive. He wanted to establish a longer, more ambitious race, one that would involve the interior villages where sled dogs had been used for so long. With the help of other mushers, including Dick Mackey and Dan Seavey, Redington organized the first Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. It ran over 1,000 miles from Anchorage to Nome.

The first race got underway on March 3, 1973 (each year the Iditarod begins on the first Saturday in March). No one knew what to expect. Many believed the mushers might not survive the long trek through the Alaskan wilderness. Both Mackey and Seavey competed. Redington had intended to compete, but as money for the race fell short, he was forced to engage in some last-minute fundraising to help make up a shortfall in the promised $50,000 purse (he had already mortgaged his home in Knik to keep the race alive).

The first Iditarod was dedicated to the memory of Leonhard Seppala. Bib #1 was reserved in Seppala’s honor from 1973 through 1980. (Since 1980, bib #1 has been reserved for individuals, both mushers and non-mushers, who have made significant contributions to sled-dog racing.)

Dick Wilmarth, a miner and trapper from Red Devil, would go on to win the first race. It took him 20 days, 49 minutes, and 41 seconds. (Compare this to John Baker’s 2011 record-setting race of 8 days, 18 hours, 46 minutes, and 39 seconds.) The $50,000 purse was split up among the top twenty finishers. Wilmarth received $12,000.

Dick Wilmarth after winning the first Iditarod in 1973.

Iditarod Trail Committee, Inc.

Wilmarth would later described that first race as less a competitive sled-dog race than “a chance to spend time with friends in the wilderness.” When it was discovered at the last minute that no finish line had been put up in Nome, a quick thinker grabbed a package of Kool-Aid and poured a line in the snow across Front Street. There was only one veterinarian for 34 dog teams. (The 2013 race will have 52 veterinarians spread out among the various checkpoints.)

Over the years, the Iditarod has become a more organized, competitive race. Today’s mushers have learned from the early trailblazers how to handle the treacherous topography and unpredictable weather faced on the trail. Care and feeding of the dogs has practically become a science. Winning times have been cut by more than half and a handful of mushers have upped the ante with multiple wins. Rick Swenson holds the record with five Iditarod wins.

The purse for the race has increased too, though not by much–at least not by American sporting standards. This year’s purse is $600,000, to be split among the first 30 finishers. The winner will receive about $50,000 and a brand new truck. Only the most famous mushers are able to make a living off sled-dog racing, and even they must rely on corporate sponsorship and year-round promotion. Mushers do it for the love of dog sledding, not for the money.

The names Redington, Mackey, and Seavey will become familiar in this blog. The children and grandchildren of three of the men who helped make the race possible carry on its legacy. Joe Redington’s son, Raymie, and grandsons, Ray and Ryan, have all competed in the Iditarod. Mitch Seavey, son of Dan Seavey, won his second Iditarod this year. Mitch’s son Dallas won last year’s race. The two men have the distinction of becoming the oldest and youngest Iditarod winners. Lance Mackey, Dick Mackey’s son, is the only Iditarod champion to win four consecutive races, in 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010. Dick Mackey and Lance’s brother, Rick, are also Iditarod champions. Dick won the closest Iditarod race ever, beating Rick Swenson by one second in 1978.

Also in 1978: the federal government designated the Iditarod Trail a National Historic Trail. Joe Redington finally got his wish.

Redington died in 1999.

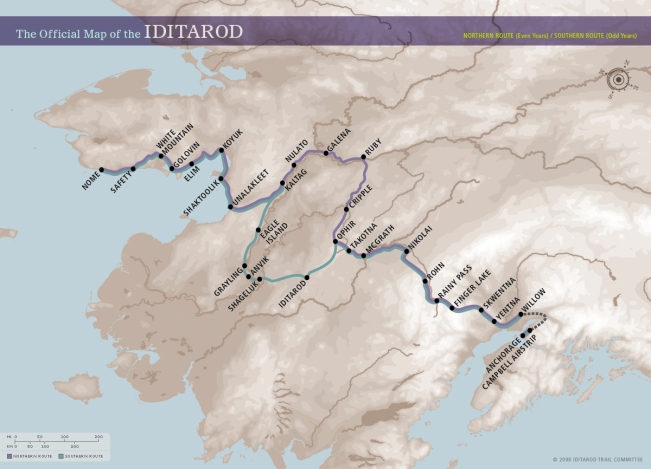

Stay tuned for my next post, which will feature a map of the race trail and discussion of some of its nastier features. And, yes, in an upcoming post I’ll talk about the dogs.